Published in 2007 by Amazon’s CTO, Werner Vogels and a group of Amazon employees, Dynamo describes a set of techniques that when combined, form a highly-available, distributed key-value data store. The whitepaper describes an internal technology, which is used to power parts of AWS, most notably their S3 service. It should be noted that although they share a very similar name, Dynamo as described in the paper and this blog post is not the same technology as AWS DynamoDB.

Dynamo is:

-

Decentralised: Each node in a cluster carries the same responsibilities and offers the same functionality. The system is entirely peer-to-peer and there is no concept of leader or follower nodes.

-

Highly Available: Dynamo distributes its data across its nodes and manages multiple replicas. Every node can service reads and writes of data by forwarding requests onto those that store the data.

-

Scalable: Read and write throughput can be increased or decreased linearly by adding or removing machines from the cluster. Dynamo is able to seemlessly handle redistribution of data to account for such changes and scaling a cluster requires no downtime and little operational overhead. Data redistribution also has the effect of reducing the amount of data that individual nodes must store.

-

Fault Tolerant: Data is decentralised and replicated between multiple nodes to provide redundancy. Subsets of data can only become unavailable if all of its replicas are unavailable. Dynamo can be configured to replicate data to nodes hosted in different geographically located data centres meaning that a cluster can withstand the loss of entire data centres while still remaining available.

-

Eventually Consistent: One of the key aims of Dynamo is to provide an always available and always writeable data store, therefore the consistency of data is sacrificed in favour of availability. At a given point in time, replica nodes for a given data item may disagree on the value of a given key, but updates will eventually reach all replicas.

There are many challenges that distributed databases face that their non-distributed counterparts do not. This post aims to summarise how Dynamo approaches these problems in a digestable way.

Data Partitioning

Dynamo dynamically partitions (shards) data across all of the nodes in a cluster. For redundancy and availability it additionally houses a configurable number of replicas of each data partition on separate nodes. The problem is, how does Dynamo know which nodes should house a given object?

Consistent Hashing

To decide where a piece of data should live in a cluster, Dynamo uses a technique called Consistent Hashing. The key of the object is run through a hashing function to deterministically derive a number, which is subsequently mapped into a position on a theoretical ring. The node which should house the information is then determined by finding the next node (which also sits on the ring) in a clockwise direction from that position. A benefit of Consistent Hashing, is that during a resize of the cluster (adding or removing nodes), only a small subsection of items need to be moved to different nodes.

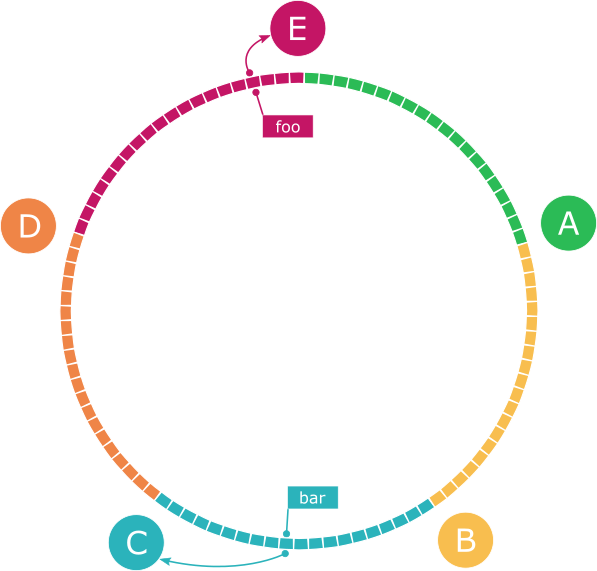

To illustrate, let’s take a ring of 5 nodes with an address space of 100 partitions, numbered from 0 to 99. Assuming that we’d like a relatively even distribution of data, we could arrange the nodes like this:

| Node | Position | Range |

|---|---|---|

| A | 19 | 0 - 19 |

| B | 39 | 20 - 39 |

| C | 59 | 40 - 59 |

| D | 79 | 60 - 79 |

| E | 99 | 80 - 99 |

Now lets say that one of our nodes (it doesn’t matter which) receives a couple of requests to store objects with keys "foo" and "bar" in our cluster. In order to determine where each object should be placed, the node hashes the key (and in our case uses the modulo operation to get a number between 0 and 99), and then looks up which node should own that object from our table:

public int hash(String key) {

MessageDigest md5 = getMD5();

md5.update(key.getBytes());

BigInteger result = new BigInteger(md5.digest());

return result.abs().mod(BigInteger.valueOf(100L)).intValue();

}

private MessageDigest getMD5() {

try {

return MessageDigest.getInstance("MD5");

} catch (NoSuchAlgorithmException e) {

throw new RuntimeException(e);

}

}

Any hashing algorithm could theoretically be used. However, Dynamo opts to use MD5, so we’ve used Java’s MessageDigest class, specifying the MD5 algorithm, to illustrate in the code above. MD5 returns a 128 bit (16 byte) number so we’ve used BigInteger represent it, used its abs method to ensure that the number is positive and finally its mod method to apply the modulo operation and get a number between 0 and 99.

Hashing "foo" and "bar", we get positions 96 and 50, respectively, which correspond to node E for "foo" and C for "bar".

Replication

When scaling a relational database it is common to replicate the entire dataset to separate multiple nodes and have them serve as read replicas, where only a single instance manages writes and then replicates that data to each replica. In Dynamo, the data is partitioned/sharded across all of the nodes in the cluster as described above. Each distinct shard is individually replicated to other nodes.

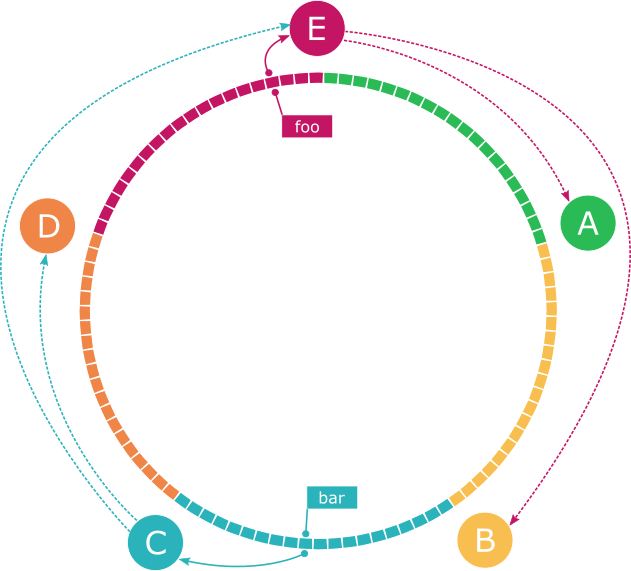

During a write, the object will be replicated to N-1 nodes clockwise from the selected node, where N is a configurable replication factor. In the previous example, given an N value of 3, the data identified by the key "foo" which is written to node E, would be replicated to nodes A and B. Similarly, the data identified by the key "bar" which was written to node C, would be replicated to nodes D and E.

Reading and Writing

In the previous section we discussed writing and how Dynamo decides where objects should be stored, however, this is only part of the story.

Vector Clocks

Dynamo provides eventual consistency, which means that a write can be considered complete before it has been propagated to all replicas and subsequent reads may return an object that doesn’t have the latest updates. In addition, issues such as network partitions or node failures may mean that updates are not propagated for a long period of time. Dynamo endeavours to always stay available and writeable, even during failures, which means that it is possible for different nodes to hold conflicting versions of an object.

In order to manage the very real risk of conflicts arising, individual Dynamo nodes use Vector Clocks to record causality between different versions of an object. Instead of just the value itself, a list of pairs consisting of a node identifier and a counter are stored alongside it. This additional information effectively represents a local version history of the object which can be used to detect conflicts.

To illustrate, let’s use the "bar" example from earlier, which hashes to a position managed by node C and its replicas D and E.

-

A client sends a request to write

"bar"with a value of100, which is picked up by node C. C increments an internal sequence counter and writes the value along with a newly created vector clock:[(C, 1)]. This update is replicated to D and E.Node Key Latest value Vector Clock C "bar"100[(C, 1)]D "bar"100[(C, 1)]E "bar"100[(C, 1)] -

The same client sends another request to write

"bar"with the value200. This request is picked up by node D. D updates its internal sequence counter, writes the new value and updates the vector clock:[(C, 1), (D, 1)]. This update has not yet been replicated to other nodes.Node Key Latest value Vector Clock C "bar"100[(C, 1)]D "bar"200[(C, 1), (D, 1)]E "bar"100[(C, 1)] -

At the same time a different client reads and then sends a request to write

"bar"with the value300to node E. Currently, E only knows about the update carried out by C. It updates its internal sequence counter, writes the value locally and updates the vector clock:[(C, 1), (E, 1)].Node Key Latest value Vector Clock C "bar"100[(C, 1)]D "bar"200[(C, 1), (D, 1)]E "bar"300[(C, 1), (E, 1)] -

At this point nodes D and E are in conflict. Both D and E contain

(C, 1)in their vector clocks, but D’s clock doesn’t contain a value for E and E’s clock doesn’t contain a value for D. They have diverged and cannot be syntactically reconciled. -

A client now reads

"bar"and receives multiple versions of the object that it must reconcile. Once the client has decided on the correct value, it writes it back to the system. Let’s say this write is coordinated by node C and the value chosen by the client to resolve the confict is 300. C increments its own internal sequence counter, writes the new value and merges the vector clock:[(C, 2), (D, 1), (E, 1)].Node Key Latest value Vector Clock C "bar"300[(C, 2), (D, 1), (E, 1)]D "bar"200[(C, 1), (D, 1)]E "bar"300[(C, 1), (E, 1)] -

The conflict is now resolved. Once D and E receive the update from C they can tell from the vector clock that the conflict has been reconciled and can then update their own values and vector clocks to match.

Node Key Latest value Vector Clock C "bar"300[(C, 2), (D, 1), (E, 1)]D "bar"300[(C, 2), (D, 1), (E, 1)]E "bar"300[(C, 2), (D, 1), (E, 1)]

Consistency

Any read or write in Dynamo can be handled by any node in the cluster. Consistent Hashing is used to identify the target nodes, and the request is forwarded, usually to the first healthy node in that list. The node handling the request is known as the coordinator.

In order to maintain consistency across the replicas of each data shard, Dynamo uses a tunable quorum-like protocol consisting of two configurable values, R and W.

During a write operation, the coordinating node sends a copy of the data out to all of the replicas. It waits until at least W replicas have acknowledged the write before it returns to the caller.

Similarly, during a read operation, the coordinating node requests all the latest versions of an object for a given key from each of the replicas in the list. It waits until it receives at least R responses before returning a result. If the coordinator happens to receive multiple, conflicting versions of the data that cannot be automatically reconciled, it returns those diverging versions of the data to the client. It is then up to the client to resolve the conflict and write it back.

Cluster Membership

Dynamo is a decentralised, distributed system; there is no central hub where information about configuration or the topology of the cluster can be accessed. Instead, nodes must rely on peer-to-peer communication models to gather such information.

Gossip Protocol

The Gossip Protocol, which is based on the way epidemics spread, was chosen as Dynamo’s mechanism for propagating information to nodes in the cluster.

The Gossip Protocol is a fairly simple idea. At regular intervals (in Dynamo this is usually every second), nodes will choose another known node in the cluster at random and send some information. If the nodes don’t agree on the information, they will reconcile the differences. This pattern repeats until every node in the cluster eventually has the same information.

Updating Membership

The Dynamo Paper explains that Amazon decided to opt for a manual approach of adding or removing a new node from the cluster. An administrator would use a tool to connect to an existing node and explicitly issue a membership change to add or remove a node. That membership change will be propagated throughout the cluster via the Gossip Protocol. For example:

- An administrator sends a request to node A that node F is joining the cluster.

- Node A updates its membership records.

- Using Gossip, node A sends its membership records to node B. Since B does not know about F, it updates its own records.

- On the next iteration, nodes A and B contact nodes C and E who also update their local membership records.

- On the next iteration, all 4 nodes, A, B, C and E choose other random nodes to send messages to. Node C chooses to contact D, which is the only node that doesn’t yet know of F. Node D follows the same procedure and updates its records.

- Now, all of the nodes in the cluster have learned about F and the cluster is eventually consistent.

Upon starting for the first time, the new node chooses its position in the consistent hash space and uses the Gossip Protocol to propagate this information. Eventually, all nodes in the cluster will become aware of node F and the ranges of data that it handles.

Handling failure

Dynamo was designed from the beginning with the expectation that things will go wrong. Aside from the techniques we’ve already discussed such as data partitioning and replication, there are other approaches that Dynamo takes to explicitly handle failures.

Sloppy Quorum and Hinted Handoff

Taking our examples from earlier, imagine we have a 5 node cluster and a request to write a value with the key "foo". We determined previously that this key would be coordinated by node E and subsequently replicated to nodes A and B given our replication factor of R=3. We’ll assume a write consistency of W=2, which means that the coordinator and at least one other node must acknowledge the write before E can to respond to the caller.

The data centre hosting nodes A and B suffers an outage and E is unable to replicate the value to either node. Instead of allowing the write to fail, Dynamo will instead walk the ring and try to send the replicas to nodes C and D. Once the delivery has been acknowledged by one of these two nodes, E is able to return to the caller. This is known as a “sloppy quorum”.

Given that C and D are not normally responsible for storing objects in this space, they will instead commit them to a separate local database, along with a hint that specifies which node was the intended recipient. They periodically check to see if A and B have recovered and will deliver the data to them, before deleting from their local stores. Through this process known as “hinted handoff”, data can be durably written to multiple replicas even in the face of failure.

Anti-entropy with Merkle Trees

Merkle Trees are used in Dynamo to identify any inconsistencies between nodes. Individual nodes maintain separate Merkle Trees for the key ranges that they store and they can be used to quickly work out if data is consistent and if not, identify which pieces of information need to be synchronised.

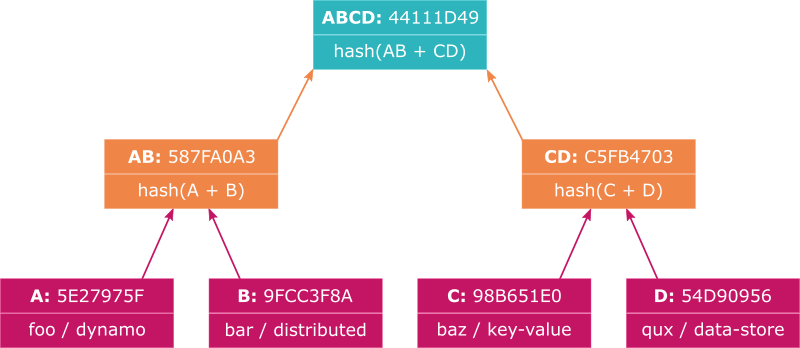

A Merkle Tree is a tree in which leaf nodes represent the cryptographic hashes of individual data items and every subsequent parent of those nodes are constructed by hashing together the concatenated hashes of its children.

Let’s take an example of a dataset containing 4 items, with keys foo, bar, baz and qux. We’ll take the MD5 hash of the values of each of those items and they will form the leaf nodes of our tree (we’ll call the hashes A, B, C and D for brevity):

| ID | Key | Value | Hash of value |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | foo |

dynamo |

8933720b03f432b3fe3877635e27975f |

| B | bar |

distributed |

8201b6e3d88dd2de76c3ccec9fcc3f8a |

| C | baz |

key-value |

ebe3c14547dfc740c784bcaf98b651e0 |

| D | qux |

data-store |

a31c72b5b6c452fd2a48db1554d90956 |

Now we construct a parent of A and B by concatenating the hash of A and the hash of B, then running it through the same hash function. We’ll do the same with C and D:

| ID | Hash |

|---|---|

| AB | 9000b49006fd54bfc61819c8587fa0a3 |

| CD | 2eb4dbe7afe78e9096af2b99c5fb4703 |

Finally, we get to the root of the tree by concatenating AB with CD and then hashing the result: b09649f6104fd73b8f7ca2e544111d49

Let’s say that the Merkle Tree shown above is maintained by node A and we’re comparing it with node B. Node A might request node B’s root hash and upon receiving it, compares it to its own. If the hashes match, we can be sure that both nodes contain the same data.

Let’s assume that the hashes don’t match and node B’s root hash is db0082ff1fecd03712bd03cb11f0a1c3. The hashes for the level below the root are then requested from node B which responds with 9000b49006fd54bfc61819c8587fa0a3 and 50f45bad13b3d4f2c59ebbe961f083ad respectively. The first hash, 9000b49006fd54bfc61819c8587fa0a3 matches the left side of node A’s tree, but the second hash is different. This means that the data on the left side of the tree is the same on both nodes.

Moving forward, node A would then ask B for the hashes for nodes under 50f45bad13b3d4f2c59ebbe961f083ad. Node B would then respond with ebe3c14547dfc740c784bcaf98b651e0 and 29e4b66fa8076de4d7a26c727b8dbdfa. The first hash matches the hash in node A’s tree for the value with the key baz but the second hash does not match. This indicates that the value for qux must be updated.

By maintaining Merkle Trees, Dynamo nodes are able to quickly find out which objects do not match between nodes and can then take action to synchronise. This approach avoids the need for nodes to send around entire datasets before it is necessary to do so, at a reasonably small overhead.

Wrapping up

Most of the techniques described in the Dynamo paper have actually been around for some time in the computing world, but the way in which they were combined and used to create a fault-tolerant, scalable, distributed database was quite revolutionary.

The paper has helped to shape the distributed database space and has contributed to the field’s need to adapt to a world that is ever more demanding of performance and availability. Dynamo is the foundation of numerous propietary and open-source projects in the wild, such as:

- Apache Cassandra, which was co-authored in 2008 by one of the original Dynamo authors while working at Facebook

- Project Voldemort, released in 2009 by LinkedIn

- Riak, developed by Basho Technologies in 2009

If you’d like to learn more about Dynamo, I’d recommend giving the paper itself a read or by checking out this fantastic talk given by Christopher Batey at Øredev 2015, which really helped me understand some of the key concepts.